The history behind the Marquette & Jolliet Expedition

What is this celebration in honor of?

On June 16-18, 2023, we will celebrate the 350th anniversary of the 1673 expedition by Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette’s landmark expedition that led to the claiming of the entire land and water mass interior of what we now know of as America for Louis XIV, King of France.

They will be reenacting and commemorating the achievement that Jolliet and Marquette accomplished to open up and expand the kingdom of New France.

A group of individuals will be reenacting and commemorating this event by making Prairie du Chien one of it’s main stops during their voyage during the June 16-18, 2023 event.

What is the history behind this expedition?

The history of Marquette and Jolliet’s Expedition can’t begin in 1673, it must begin with the people that already inhabited the area where the rivers merged.

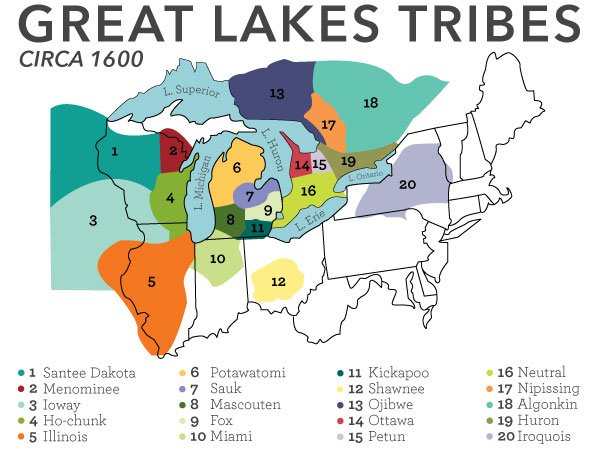

Successive Native American cultures have lived and prospered here for more than 10,000 years.

Some built mounds that still stand on the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River. Some also left behind artifacts like the stone spear points in the Al Reed collection at the Fort Crawford Museum today.

Meskwaki, Sauk, Ho-Chunk, and Dakota people lived at or near Prairie du Chien from the seventeenth century onward.

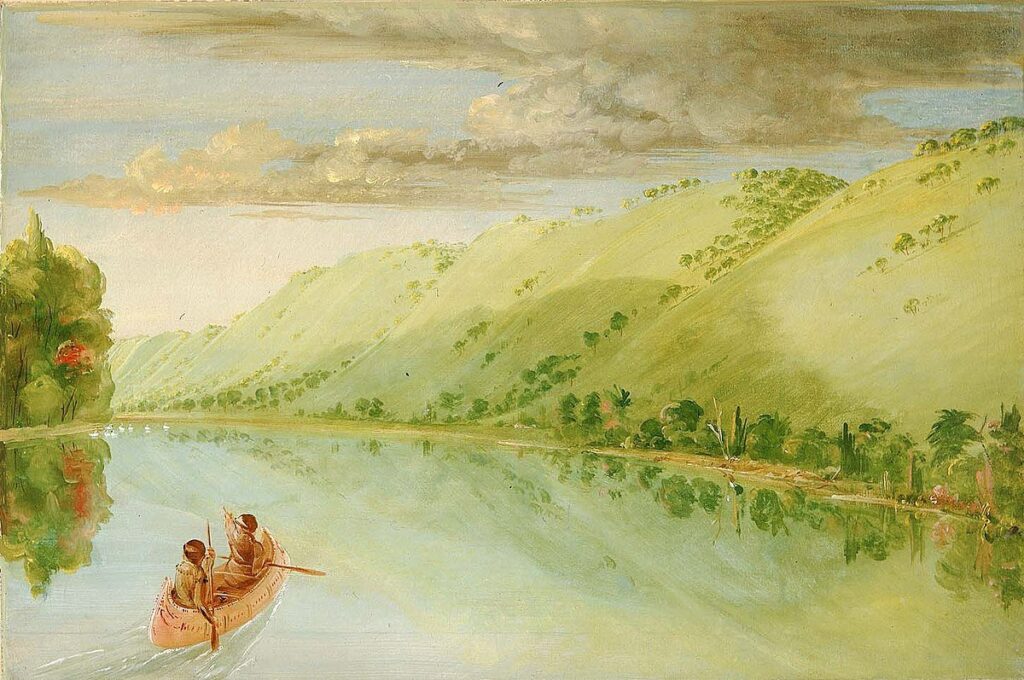

Painting by George Catlin, “Madame Ferrebault’s Prairie, above Prairie du Chien”

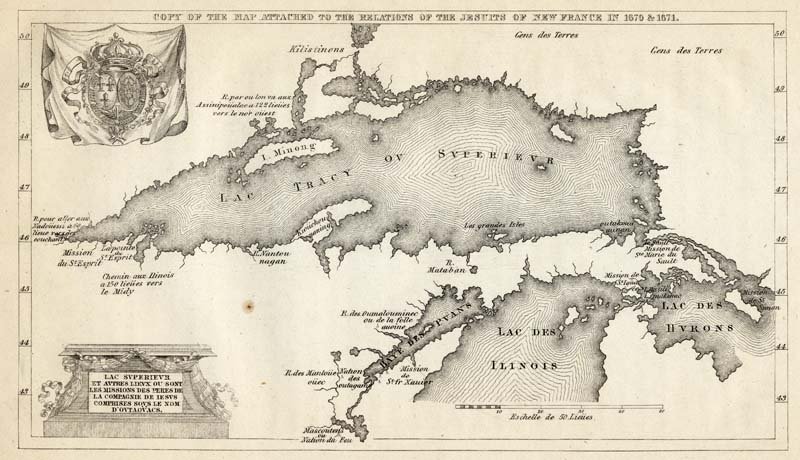

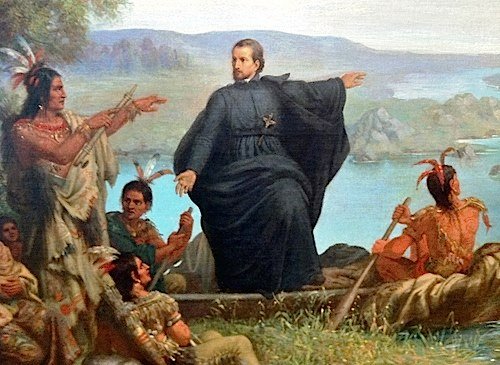

Some the first Europeans to come to the Great Lakes region were Christian missionaries. One of the most active groups was the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits, a Roman Catholic religious order that first started to preach among the Iroquoian-speaking Hurons of Lake Huron in 1625.

French Jesuit map of Lake Superior, Upper Michigan, and Wisconsin, 1600s.

The Jesuits in America used methods which were comparatively respectful of the traditional way of life of the Indians, especially compared to the approach of the Puritans in New England, who required a conformity to their code of dress and behaviour. In a simplification, the 19th-century Protestant historian Francis Parkman wrote: “Spanish civilization crushed the Indian; English civilization scorned and neglected him; French civilization embraced and cherished him.”

By 1665, they had established missions at Chequamegon Bay in Lake Superior and at Green Bay in 1669. While the Jesuits enjoyed some successes, they required rigid standards for potential converts and thus did not convert large numbers of Indians to Christianity. Whatever progress they made was lost after 1728 when they abandoned their mission stations in Wisconsin because of the Fox Wars, during which the Fox Indians rose up against French authority. The Fox Wars ended in the 1730s, but the French were unable to send new missionaries to Wisconsin afterward. The next Christian missionaries did not arrive until the 1820s, and they represented both the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations.

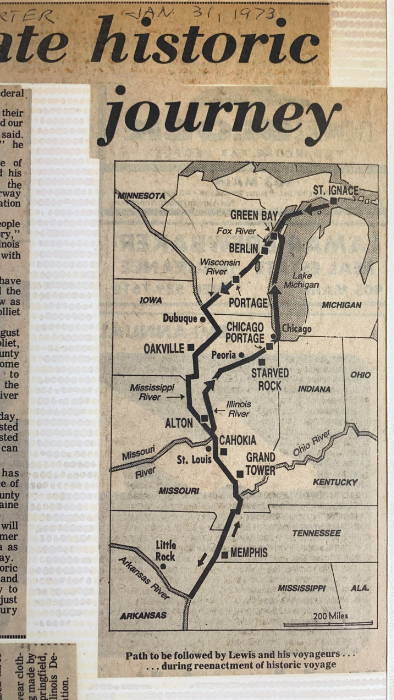

Photo of newspaper clipping from 1973 Expedition reenactment path.

Who was Jacques Marquette?

Jacques Marquette was born in Laon, France, in June of 1637. He came from an ancient family distinguished for its civic and military services

The son of Nicolas Marquette, seigneur of Tombelles and councillor of Laon, and of his second wife, Rose de La Salle, Jacques Marquette descended from two distinguished families of warriors and officials, his father’s being one of the most ancient and prominent in the Laon district.

At 17, Jacques Marquette joined the Society of Jesus and became a Jesuit missionary. Marquette studied and taught in the Jesuit colleges of France for about 12 years before his superiors assigned him in 1666 to be a missionary to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

After Jacques Marquette studied and taught in the Jesuit colleges in France, his superiors assigned him in 1666 to be a missionary to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

He traveled to Quebec, Canada, where he demonstrated his penchant for learning Indigenous languages: Marquette learned to converse fluently in six different Native American dialects and became an expert in the Huron language.

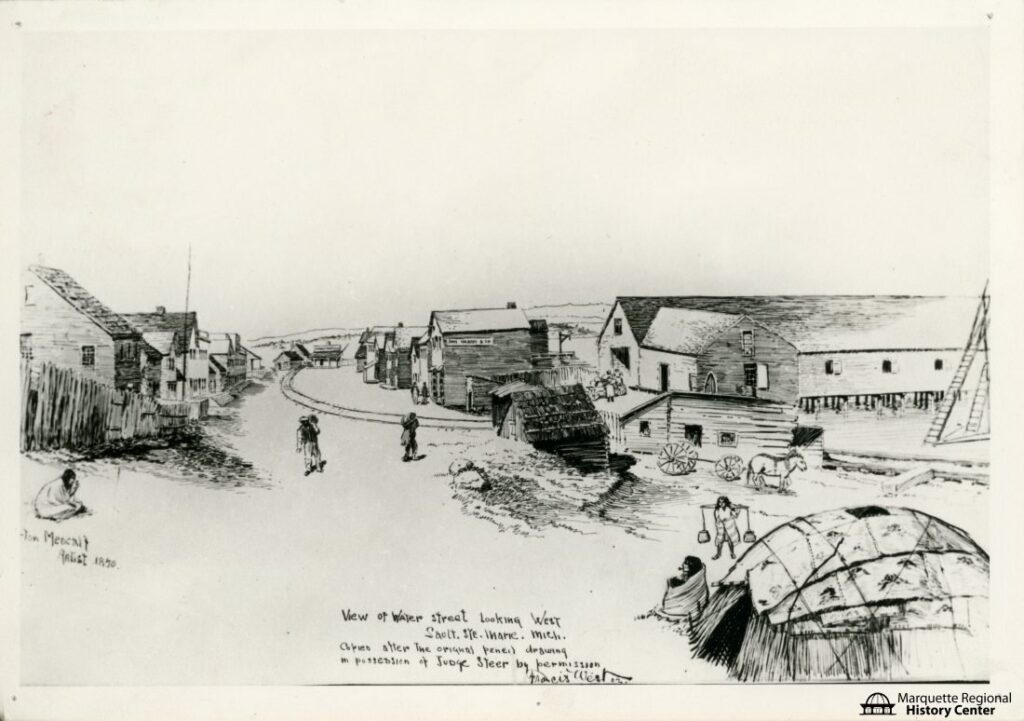

In 1668, Father Jacques Marquette left Quebec and was sent to establish more missions farther up the St. Lawrence River in the western Great Lakes region. He helped establish a permanent mission which he named Sault Stainte Marie—the state’s first European settlement — in 1668. The actions of Father Marquette set in motion events that would lead to present-day Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

In 1622, Étienne Brûlé was probably the first European to visit the area. The site is called Sault de Gaston on Samuel de Champlain’s map of 1632 (“sault” meaning “falls” in French). It became Ste-Marie du Sault when the Jesuit mission was established.

Sketch by Wharton Metcalf. “Looking west on Water Street in Sault Ste. Marie, 1850.”

In 1671, members of the Illinois tribes, told Father Marquette about the important trading route of the Mississippi River.

The Illinois Confederation, also referred to as the Illiniwek or Illini, were made up of 12 to 13 tribes who lived in the Mississippi River Valley. Eventually member tribes occupied an area reaching from Lake Michicigao (Michigan) to Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas.

The five main tribes were the Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Michigamea, Peoria, and Tamaroa. The name of the confederation was derived from the transliteration by French explorers of iliniwe to Illinois, more in keeping with the sounds of their own language.

The tribes are estimated to have had tens of thousands of members, before the advancement of European contact in the 17th century that inhibited their growth and resulted in a marked decline in population.

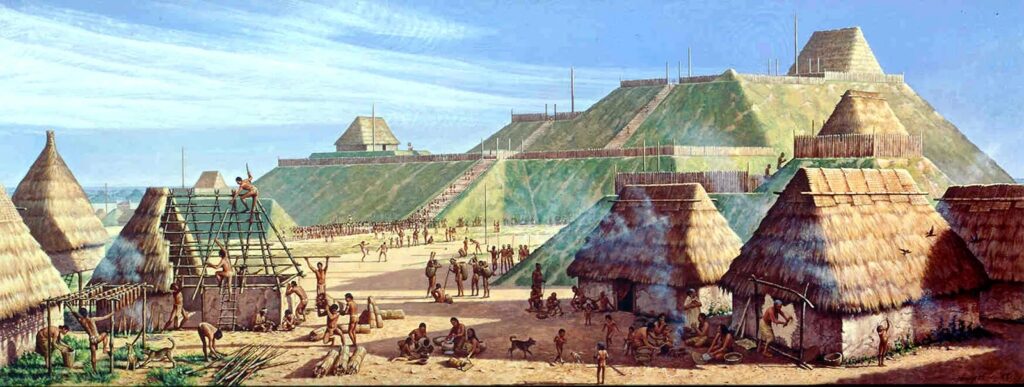

“Cahokia” Courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site; painting by Michael Hampshire

The place now called Wisconsin is the ancestral land of numerous Native nations.

Indigenous people are a part of Wisconsin’s past and present, and yet, in so many damaging ways, they have been missing from the stories we tell.

When we learn about the Expedition of Marquette and Jolliet, we must acknowledge the violent removal of Indigenous people that made European immigration possible. History often fails to teach us that people of Native nations are not just part of the past — they are a crucial part of Wisconsin now!

To learn more about First Nations in Wisconsin, check out

https://wisconsinfirstnations.org/

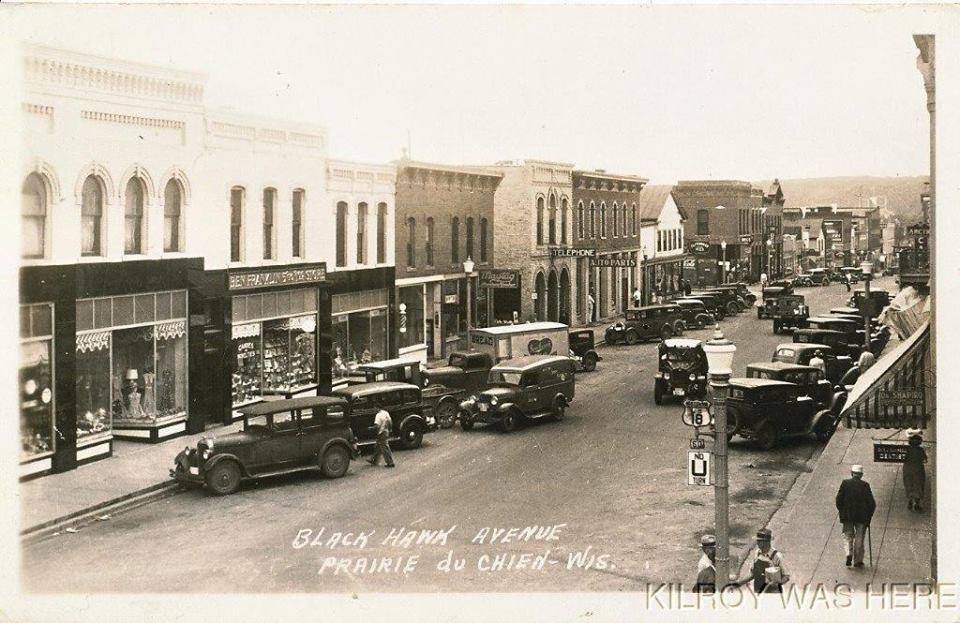

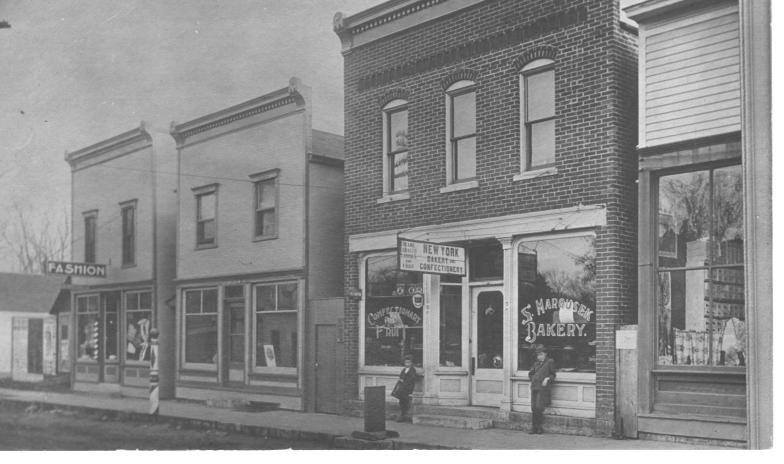

How is Prairie du Chien part of the expedition?

Prairie du Chien has its beginnings on St. Feriole Island. Several Native American mounds are located on the Island. The Island was a place of importance where various native communities would meet and trade. Very little, if any, documentation can be found about the island’s mounds.

The original Fort Crawford was actually built right on the largest mound. They may have picked the site as a means to rid the land of the indigenous peoples occupying the area at that time, as a sign of dominance, or may have just callously decided to build their fort on the highest section of land to avoid flooding.

Hercules Dousman later purchased land previously occupied by Fort Crawford and Dousman had the remains of the fort cleared away. In 1843, he built a large, brick Greek Revival house on top of the mound, which had been the site of the old fort’s southeastern blockhouse. Because of this, Hercules Dousman’s home has come to be called the “House on the Mound”.

On May 17, 1673, the Rev. Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet set out on a voyage that would take them thousands of miles into the North American interior, confirming that it was possible to travel by water from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico.

On June 15 or 17, the party entered the Mississippi River near Prairie du Chien. They continued down the Mississippi River for four hundred and thirty-five miles.

To this day, Prairie du Chien is proud to promote the historical event of Marquette and Jolliet that gave many generations the ability to transport people, products and other goods by water from the Great Lakes through the Mississippi River to the Ocean.